One reason why successful researchers are able to produce scholarship that is insightful, groundbreaking, and significant is because of the depth made possible by iterative work.

There are times when this iterative nature of research work is obvious: when a solar cell scientist writes twenty two papers on perovskite solar cells, it is evident that their papers build on previous research to make real progress on issues of efficiency and stability, for example.

But there are times when it is far less obvious but no less true – take Patrick Radden Keefe’s books – I recently read his reporting on the history of Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family’s involvement in the opioid crisis created by Oxycontin. His previous book, before Empire of Pain, was Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland.

And sure, they are vastly different topics. Keefe started working on Empire of Pain in 2016, before Say Nothing was even published. He began writing about drugs traded across the US-Mexico border, trying to see these criminal organisations as businesses (Afterword, Empire of Pain). In his research on the business practices of huge drug cartels, he finds an increasing shift towards heroin that is found to be a reaction to OxyContin. After having investigated the fact that these drug cartels often worked like “legal commodities enterprises” it was easier for Radden Keefe to also see that Purdue was operating much like a drug cartel. And so his story was born.

My point is that whether an earlier research is DIRECTLY related to future research or whether that connection is less linear, good topics and research questions almost always come from previous readings, observations, investigations, and other ways of knowledge building.

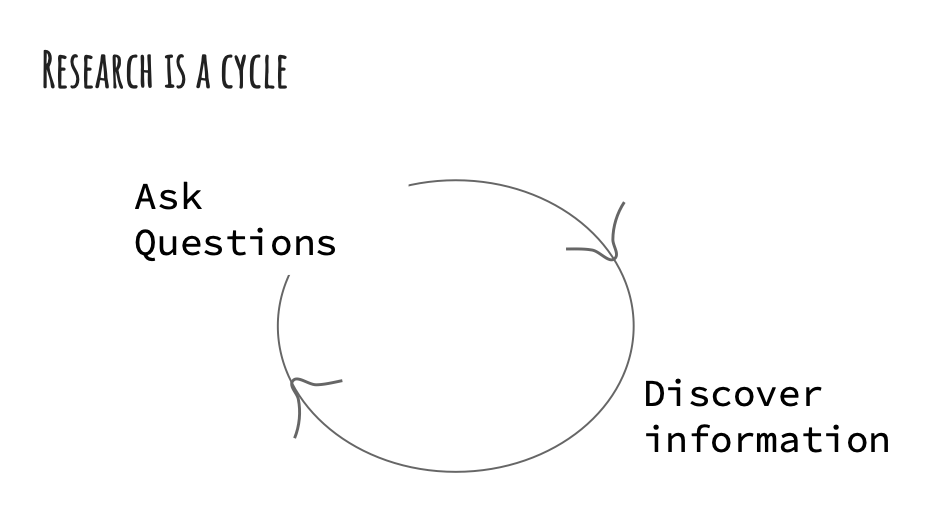

In helping students to understand the research cycle, I teach a few lessons.

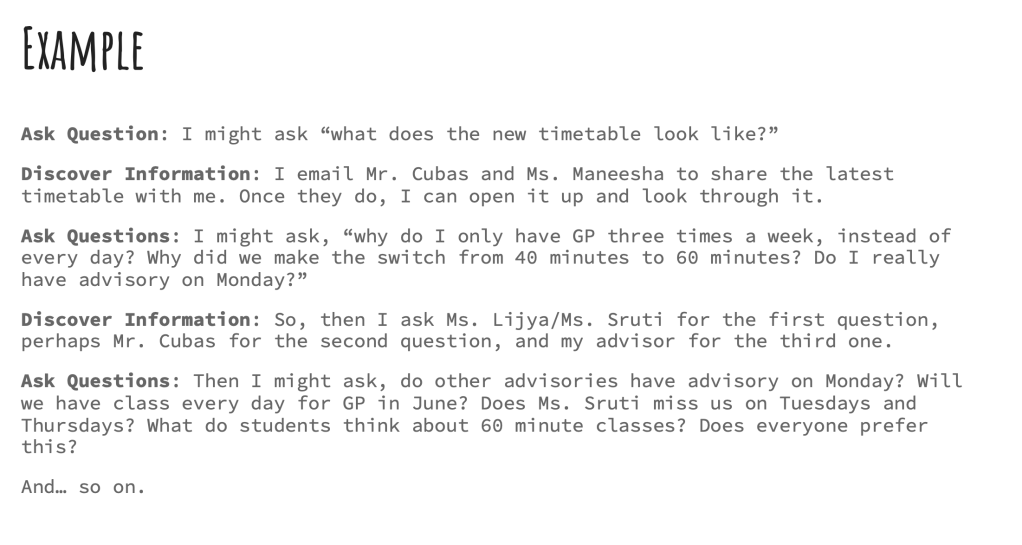

First, I talk students through the two slides below, which I use to explain the importance of having background information to generate increasingly sophisticated questions.

Second, I adapt the Question Formulation Technique for my research classroom, and have us generate questions to study schools, schooling, and education. I always start with education examples in my classroom because I think it equalizes the playing field – everyone has been a student and thought about education, so everyone has good ideas that don’t depend on academic performance as other topics might.

Then, I have us read something. Some favorite assignments include the introduction of Carla Shalaby’s Troublemakers, Joseph Henrich’s WEIRD article, and Lucy Tse’s article on heritage languages. The goal with these lessons is for students to notice how the quality of their questions shifts after they have really read and explored something. I ask them to once again follow the question formulation technique after we have read one or more texts — I want students to really see their own thinking change in terms of depth, specificity, and knowledge.

How do these questions change?

It isn’t just that their questions are more specific, which they usually are. It’s also that having read something on the topic, their questions are more directed and more nuanced. Their questions might start with how do we shift the mindsets of our parents? to what are the stated advantages of a high-quality education according to parents? To why are there differences between Himachali and Maharashtrian parents when asked about the importance of standardized test scores?

To go from the first question to the third is to move from newcomer to researcher, and that shift requires background knowledge.

Third, I assign Robert Caro’s article, “The Secrets of Lyndon Johnson’s Archives” published in The New Yorker. Here are the questions I asked students one year as they read:

- What, according to Robert Caro, are some of the principles behind his research? What are his rules and beliefs?

- Obviously, you can’t spend 10 years researching your report – what is something you can apply from this article to your own work?

- Which methods did Caro use? How did he go about conducting his research? In other words, what did he actually do?

- In what way was Caro’s process an example of “research is a cycle”?

I love this assignment. Robert Caro does a wonderful job of explaining his methodology in a way that is engaging, clear, and fun. Every time I assign it, my high schoolers can feel the itch he describes and automatically begin considering topics where they might feel a similar thrill in research and investigation.

[…] Understanding the research cycle […]

LikeLike